The End of Anger

Author note: this excerpt from A Heart Blown Open is read in its entirety in the live reading at the very bottom of this page.

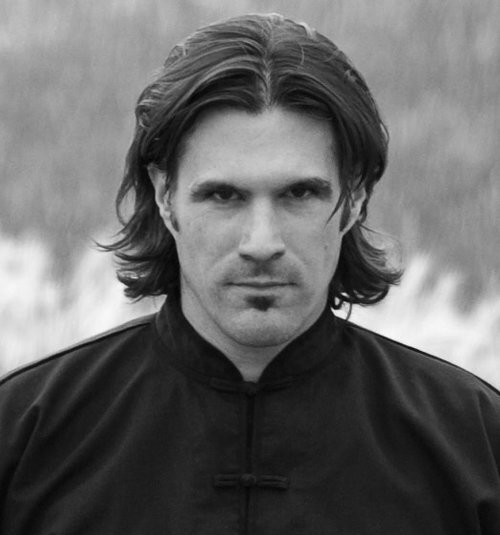

In the winter of 2007–2008, I was involved in a very intense and challenging relationship. Although we cared deeply for each other, we also fought harder and more frequently than in any relationship I’d had before (or since), which was greatly confusing to me. When Kelly was back in Boulder not long after the New Year, I requested that we meet, in part so that I could come to understand my role in my intimate relationship more clearly. He invited me up to a mountain home outside the hills of Boulder, where he was staying. I drove up, parked, and was greeted by Kelly, who was wearing the plain black pants and top common in Zen.

“Come on in,” he said casually, and directed me to a place where he had set up two meditation cushions. I took my seat, and Kelly sat down across from me.

We made small talk about our lives; I told him of my recent divorce, my life as a recently published author of fiction, and the turbulence of my current relationship. He shared some stories of his own, and we laughed and connected like two old friends. Between us sat a beautiful Japanese bowl, and with a subtle straightening of his back, Kelly struck it with a wooden handle.

“So,” he said, his face growing more serious. “Is there such a thing as pure listening?”

“Pure listening?” I asked, smiling. “Like what?”

“Can you just listen?” he asked, “Simply receive the sound of this bowl ringing?”

I listened, and nodded unsurely. A few minutes passed.

“Mind if I lead you a little,” he said, smiling a little.

“Please.”

“So just stop the sound,” he offered. “Go ahead. Don’t let it in.”

“Okay,” I said, getting the point. “I can’t stop hearing the sound.”

“I’ll ask again: is there such a thing as pure listening, outside of your ego and your story? Is there such a thing as listening without valuation, without form, without thought?”

He struck the bowl forcefully as his eyes, blue and remarkably clear, bore into mine. I heard the sounds coming from the bowl, entering my ears, and registering in my brain. He struck it again, and I began to feel the ringing in my body, as if I were listening with my heart, not my head.

“Is there such a thing as pure listening,” he asked, quietly. I did not respond.

Gradually, as I listened more closely, the beautiful bowl’s vibration began to change. I no longer perceived the sound striking my ears and entering my brain; instead, I felt the sound radiating out from my heart to the bowl, and from the bowl through me. He struck the bowl again. I was the sound itself, and the sound was me — there was no listener and nothing to hear, there was only the undulating vibration moving through the room.

I nodded my head very slowly.

“Good,” Kelly said, tracking me. “Good. Now, give me your eyes.” I looked up.

We sat, a foot apart, for nearly an hour, eyes locked onto each other, Kelly striking the bowl every minute or so.

“What is this place?” he asked eventually, his voice reverberating deeply in my chest. “Describe it to me.”

“It’s vast,” I whispered, barely able to speak. “Vast.”

He nodded.

“It’s peaceful.”

He shook his head. “Peace arises from this place. Go deeper.”

I did. “It’s still. Unmoving. Timeless.”

He smiled, and nodded.

“Deathless. Fearless. Immutable.”

“Does this place come and go?” he asked.

I smiled. “No,” I said, without hesitation. “It’s beyond time.”

Kelly nodded. “That is your experience now? Right now?”

I nodded.

“Show me. Show me without words.”

I smiled, leaned in toward him, and snapped my fingers. He smiled.

“Does this place come and go,” he asked again.

“No.” I was absolutely certain of my answer.

“Who comes and goes?”

“I do,” I said, amazed at my answer. “But this place is beyond just me. It’s the space out of which I arise.”

“From this place,” he said, cocking an eyebrow. “Can anyone make you angry?”

I thought of my girlfriend, who made me angry in the most infuriating of ways. The state of consciousness I had just explained to Kelly collapsed completely, and I nodded aggressively. “Of course,” I said, eyes narrowing, pulse increasing. “Of course! I mean, that’s why I’m here. I told you how she can really get under my skin. Yesterday, for instance…”

Without warning, Kelly took the wooden stick used to ring the bowl, and his arm flashed up and struck me across the temple, turning my head to the side from the force of the blow.

My temple buzzed, and I left my head tilted to the side as thoughts and feelings flooded me. I couldn’t believe it. I really couldn’t believe it. This old geezer had just hit me; me, a trained Shaolin Kung Fu master and tournament fighter with almost two decades of training under his belt and thirty years his junior. He hit me. My Catholic teachers used to hit me because they too thought they knew better, and I felt rage and indignation boil over in my belly. Fucker, I thought. With what bordered on hatred in my eyes, I raised my gaze to him, defiant, forceful, angry.

What greeted me froze that story in-place: Kelly had tears in his eyes, and had leaned in so close our noses almost touched. I could feel his heart, feel his compassion toward me, feel his deep desire to have me get what he was trying to show me. I felt no smugness, no judgment from him, no patriarchal zeal or arrogance, only love and devotion and complete service.

Speaking very slowly, his voice trembling with emotion, he asked me again. “Brother,” he whispered, “this is life and death; get this: can anyone make you angry?”

In a flash I saw it. I had chosen anger when he had struck me, but he had struck me out of service and love, and because he knew I could take — and needed — a punch. He very, very rarely does this sort of thing. He couldn’t make me angry. My girlfriend couldn’t make me angry. Only I could make me angry, no matter what came my way. Anger was the choice, the habituated reaction, but he had slowed down that reaction, allowing me to see what was happening in my own mind. As a martial artist, I knew that an angry warrior was a dead warrior, for the simple reason that anger overwhelms training and logic, and causes mistakes in the ring or on the streets. In Kung Fu, anger was channeled into deep clarity and presence. But I didn’t see it was the same in my intimate relationships, that the same principle was true with my girlfriend, my parents, my friends, my self. My girlfriend could never, ever make me angry; only I could do that. I understood, for the first time in my life, where Christ was coming from, his state of mind, when he said: “…do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who mistreat you. If someone strikes you on one cheek, turn to him the other also…”

“What do you really feel?” he asked.

“I care. I care so much about her,” I whispered. “I love her.”

“What else?”

“I’m afraid I’ll lose her.” I was amazed at how close to the surface those insights were, and how much I was fighting back tears.

“So you’re afraid and you care deeply, and yet you react with violence? Does that make sense to you?”

I shook my head, slowly. “It doesn’t make sense, especially since no one can make me angry but me.”

Kelly sat back, and a large smile came to his face. “That’s right, Baba,” he said. “That’s right.”

That insight, that feeling of deep love and gratitude at being struck, was only possible because from this vast, empty, quiet, fearless, and timeless place, anger was inconceivable. Not as an idea or a philosophy of peace, but as a lived reality. There simply was no room for anger in such vastness.

Kelly worked with me for another forty-five minutes before we parted company, but I was so shaken from what he had shown me that I forgot to say goodbye, forgot to offer him a donation for his services, forgot to shake his hand or hug him, forgot very nearly how to get back to Boulder. Anger had so long been a part of who I was; I was angry at my upbringing, angry at the Catholic Church of my youth, angry at my bank account, angry at my girlfriend, angry at the world, and often angry at myself. What would it mean to live in a world where anger was inconceivable?

Order the book now from Amazon.

Below, I read this excerpt (starting at 4:25).